PHILLIS WHEATLEY (1753-1784)

Phillis Wheatley was America's first black woman to be published, and the second woman to publish poetry. [Anne Bradstreet was the first.]

For most of her life she was a slave but still became a respected author and one of the best known poets in pre-19th century America. Also a loyal patriot, she was living proof for abolitionists that blacks could be both artistic and intellectual. “A person so favored by the Muses,” wrote George Washington to her in a February 28, 1776 letter, “and to whom Nature has been so liberal and beneficent in her dispensations.”

A PERSON FAVORED BY THE MUSES

Phillis was born in West Africa (probably present day Gambia or Senegal) and sold into slavery at the age of about seven. Rather than being sent to either the West Indies or Southern colonies for hard labor in the fields, she ended up with slaves sent to Boston because of age and/or frailty.

She was purchased at the Boston docks by the family of John Wheatley, who was either a prominent merchant or tailor (or both), for a pittance because the captain of the slave ship thought the girl was ill and about to die. The family named her Phillis, after the ship that brought her from Africa.

It didn’t take long for the Wheatley family to discover what a prodigy she was. John Wheatley, a progressive thinker, recognized her unique talent and supported Phyllis's education. She was released from some of her household duties to study with the Wheatley’s 18-year-old daughter Mary and their son, Nathanial. Within a year and a half she was reading the Bible, Greek and Latin classics and British literature. She also received education in other subjects such as geography, mathematics, and astronomy.

By the age of twelve, she was writing poetry about hope, freedom and morality, which her owner John Wheatley showed off to many of his friends in high places. He also allowed her to focus on her education instead of housework.

Phillis sent her first poem to the University of Cambridge-New England, Entitled “On Messers Hussey and Coffin.” In 1767, the poem was published in the Newport Rhode Island newspaper Mercury, stirring up a lot of discussion and establishing her as the first African-American to be published.

Publication of her poem “An Elegiac Poem, on the Death of the Celebrated Divine George Whitefield” in pamphlet form in 1770 by Russell and Boyles, Boston, reached Boston, Newport, and Philadelphia, and appeared alongside the funeral sermon for Whitefield in London. The poem, written in heroic couplets, describes Whitefield as bringing the voice and knowledge of God and Jesus to the Americas. Even at the age of seventeen, the poet’s spiritual language incorporates themes of inclusion and equality.

"We hear no more the music of thy tongue;

Thy wonted auditories cease to throng."

▼ Photo source: www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/phillis-wheatley

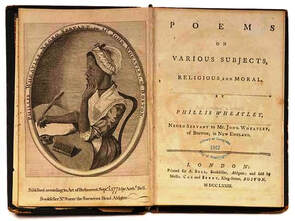

Her reputation not-with-standing, when Wheatley tried to publish her book of poetry, people questioned that an African slave could write poetry, and she had to defend her authorship in court in 1772. She won the case, and John Wheatley convinced some of Boston’s most respected men, including the governor and John Hancock, to review the work and vouch for the poems’ authenticity.

Even with that, American publishers wouldn't publish her book of poetry. The next year, in 1773 (age 20), she traveled with Nathaniel Wheatley to London where chances of publication were better. She was introduced to high society, and they were quite enthusiastic about her work.

Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon

▼Photo Source: en.wikiquote.org/Selina_Hastings

▼ Photo Source: www.osgf.org/blog/poetry-of-phillis-wheatley

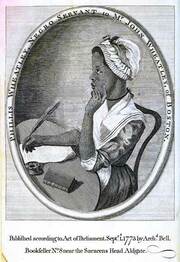

The engraved portrait of Phillis Wheatley, used as the frontispiece to her poems, Reflections on Various Subjects Religious and Moral (London, 1773), is attributed to the poet and visual artist Scipio Moorhead, a slave in Boston, Massachusetts, and a friend of Phillis Wheatley. One element of the identification of the portrait as Wheatley might have been a mention of the subject’s finger held to her cheek. This engraving has been copied many times.

Frontispiece to “Reflections on Various Subjects Religious and Moral” Portrait of Phillis Wheatley, Wheatley Hall, Univ.of Mass, copy of drawing Photo source: upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/Wheatley believed to be by Scipio Moorhead - Photo source: ▼

▼ www.massachusetts.edu/remembering-wheatley-hall-namesake

Although she had the freedom to write poetry, recited it in many places, and became well known, Wheatley was still a slave. All the money she earned went to the Wheatley estate. When John Wheatley died in 1778, five years before the state of Massachusetts outlawed slavery, his will provided for giving Phillis her freedom.

In 1778, Phillis Wheatley married John Peters, a grocer she had known for five years. Her friends disapproved of him, probably because he was ambitious and purportedly prided himself on his great business acumen. Apparently he was intelligent, personable, wrote and spoke fluently, but also tended to exaggerate his credentials, even calling himself Dr. Peters and saying he was a lawyer. John Peters Portrait ▼

Photo Source: google.com/search?biw=1360&bih/John Peters

Sources vary regarding their offspring. One indicated she lost two children. In 1784, John Peters landed in debtor’s prison and while he was still there, Phillis Wheatley died in childbirth at the age of 31. Her last surviving child died shortly afterward.

IN PERSPECTIVE

Even in her day and status, this remarkable woman achieved high and popular acclaim. American author James Weldon Johnson (1871-1938) described Phillis Wheatley as “one of the important characters in the making of American literature, without any allowances for her sex or antecedents.”

The author of https://wheatleysboston.org/ sums it up with the following:

Phillis Wheatley’s “life as a freed woman became emblematic of the experiences of freed people of color in the early republic. Though she was able to marry a free black grocer, John Peters, she struggled to make a living as a poetess.

In many ways, Phillis’s story is both unique and ordinary. Not many African slaves left written records of their experiences in the colonies, and even less had the opportunity to become published poets.

Phillis story, however, reveals the inequality that African slaves faced in colonial America. Slavery was a widespread reality in the British colonies, from Massachusetts down to Georgia. This legal and economic system served to bolster the social and economic power of the colonies’ elites. In the case of Phillis Wheatley, slavery meant having access to a literary world that highlighted her talent but benefited her masters. This inequality became most apparent when she attempted and failed to publish her poetry as a freed woman. She had little recourse but to clean homes in order to survive.”

This woman should be an American icon, and I don’t believe she is even mentioned in history courses. Fortunately, she is not forgotten, only lesser-known to the American public than she should be..

Photo source: https://friendsofthepublicgarden.org/2017/02/16/african-america-history-month-sculpture-in-our-parks/

"In every human Beast, God has implanted a Principle, which we call Love of Freedom;

It is impatient of Oppression, and pants for Deliverance." __ Phillis Wheatley

Sources:

http://www.artfixdaily.com/blogs/post/873-phillis-wheatley-or-dido-elizabeth-belle

https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Phillis_Wheatley

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/phillis-wheatley#tab-poems

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/phillis-wheatley

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phillis_Wheatley

https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/phillis-wheatley

https://npg.si.edu/blog/phillis-wheatley-her-life-poetry-and-legacy

https://www.biography.com/people/phillis-wheatley-9528784

http://www.pwacleveland.org/bio

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/phillis-wheatley

https://www.osgf.org/blog/making-a-new-america-the-poetry-of-phillis-wheatley

https://mmofraghana.org/uncategorized/sailing-on-a-name-phillis-wheatley-and-sarah-bonetta/

https://www.grossmont.edu/people/karl-sherlock/english-231/notes-exercises/phillis-wheatley.aspx

https://wheatleysboston.org/

https://blog.oup.com/2017/02/john-peters-phillis-wheatley/

https://edu.glogster.com/glog/phillis/26ipov87mnw?=glogpedia-source

https://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/phillis-wheatley-106.php

http://www.phillis-wheatley.org/poetry-and-fame/

https://twitter.com/pardlo/status/900186009366908929

Photos

https://www.google.com/search?biw=1360&bih=657&tbm=isch&sa=1&ei=38iTXJ38DY3AsAXK86sw&q=John+Peters%2C+husbANd+of+phillis+Wheatley&oq=John+Peters%2C+husbANd+of+phillis+Wheatley&gs_l=img.12..35i39.6249.22013..24817...0.0..0.199.4250.11j29......1....1..gws-wi

https://www.gamecareerguide.com/features/816/results_from_game_design_.php?print=1

RSS Feed

RSS Feed